Chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis (CVVC)

If you are a woman stuck in endless, chronic vulvovaginal pain…if you think it all started with a yeast infection (even if tests are now perhaps negative)…maybe you’ve been diagnosed with “vulvodynia”…but none of the other treatments have worked so far…welcome!

This is a resource website for women suffering from chronic vaginal yeast infections, the healthcare practitioners treating them, and anyone interested in learning more about this condition. This condition is extremely painful, underdiagnosed, and there are countless women who need help. It will not always show up positive for candida species on vaginal swab cultures, even the comprehensive microbiome tests — but it is estimated to affect millions of women. And this condition is fully treatable.

Resources and information on this website are entirely based on a careful review of many published research papers and studies (all works are cited), reported clinical observations in real-world medical practices, and conversations with experts in CVVC.

Your pain is real. And you do not need to live with your pain forever.

Far too many women with CVVC are misdiagnosed, given the wrong treatments, and stuck in a cycle of debilitating pelvic pain for years.

We must change that.

What is chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis (CVVC)?

Vaginal yeast infections (vulvovaginal candidiasis, or VVC) affect an estimated 75% of women at least once during their lifetime (1). These infections are caused by the yeast organism candida, which is normally found in the vagina but can sometimes overgrow — leading to symptoms like burning, itch, discharge, soreness, painful sex, and swelling. Candida albicans causes a vast majority (85-95%) of vaginal yeast infections, but other species such as candida glabrata, candida parapsilosis, and candida tropicalis can also cause infections (2). There are subtypes of VVC, known as recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) and chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis (CVVC). RVVC is defined as four or more discrete episodes of VVC in one year, where women are asymptomatic between infections (3). RVVC is estimated to affect up to 9% of women (4).

When it comes to CVVC, women are symptomatic all of the time, as this disease is continuous and unremitting. CVVC affects a small percentage of women, and is a hypersensitivity response to small amounts of candida that can remain in the vagina after an acute infection and invade vaginal wall tissues where they continuously cause inflammation (5, 6). Think of CVVC like an allergy, where the body has an exaggerated immune response to an otherwise commensal (harmless) organism. These women are unable to tolerate even the smallest amounts of candida, and may experience significant vulvovaginal inflammation and pain in response.

Very often, this condition occurs after an acute VVC infection and vaginal testing swabs can be false-negative, despite severe symptoms and pain (7). The absence of a positive swab does not rule out this condition — in fact, you should expect swabs to be negative. The swabs can be negative due to treatment with antifungals (e.g., fluconazole), low levels of candida that fall below a diagnostic testing threshold, or candida that embeds inside the vaginal tissues (5, 6). It usually requires long-term treatment with an oral antifungal (e.g., daily fluconazole for 3 months) to resolve symptoms (5). Due to its ability to evade detection on standard vaginal swab tests, this disease is terribly misunderstood, misdiagnosed, and leaves many women in pain for years. It is often diagnosed as “vulvodynia”, which means chronic pain of the vulva — however, many doctors fail to recognize the underlying candida that is causing a woman’s long-term pain. The age of symptom onset is usually years or decades before a woman is diagnosed correctly (2).

In certain cases, a vaginal yeast infection that is left untreated for more than 6 months can cause activated mast cells (a type of immune cell that plays a key role in allergic reactions) to produce something called nerve growth factor (NGF). The NGF causes new nerve endings to sprout, leading to too many pain nerve endings around the vaginal opening (8). This process is called neuroproliferation. Once neuroproliferation has occurred, the infection may be more difficult to treat. However, there are countless women who have fully healed from CVVC despite having the infection for YEARS — and it is important to remember that nerves will heal with the right treatment.

The bottom line: If chronic vulvovaginal pain started with a yeast infection, and the symptoms do not fully resolve with a standard course of antifungal treatment, CVVC should be suspected.

Why does CVVC happen to some women and not others?

For women with CVVC experiencing vulvovaginal pain, it can very often feel like “why me?”. We see other women recover quickly from acute yeast infections after popping 1 fluconazole pill, but we are still left with significant burning pain after standard treatment. The answer lies in our genetics!

Women who develop CVVC have a polymorphism (a gene variation) that causes this hypersensitivity (overreaction of immune system) to candida —leading to chronic inflammation (2, 8). It is just like an allergy, and often occurs in otherwise healthy women who are not immunocompromised (5). Standard antifungal treatment for yeast infections (e.g., 1 fluconazole pill) is insufficient in resolving symptoms for this population of women, because it does not eradicate all the yeast cells. For a vast majority of women, low levels of candida in the vagina (e.g., left over from an acute infection) do not cause symptoms because their immune systems are able to tolerate it. For women with CVVC, the persistence of candida in vaginal tissues causes chronic inflammation and pain because our immune systems are NOT able to tolerate it — even at the extremely low level of less than 100 candida cells! This tiny level of yeast is very unlikely to show up on standard tests (9).

So, do not blame yourself for being unable to clear a yeast infection! It is nothing you did wrong. It is all in our genetics — and you can instead blame polymorphisms in genes that control inflammation, such as IL1-RA (2, 8).

Yeast infections also only occur in the presence of estrogen, and studies show they only happen after menopause if a woman is taking estrogen replacement therapy (10). Estrogen in the body stimulates the storage of glycogen (a carbohydrate) in vaginal epithelial cells. This glycogen converts to glucose, which provides an energy source to candida species (2). This explains why CVVC symptoms are often cyclical throughout the menstrual cycle, worsening in luteal phase when glycogen storage is highest (5).

What are symptoms of CVVC?

CVVC is a chronic (long-lasting), non-erosive (not eroding the tissue), erythematous (red) vaginal infection that is most common in younger, pre-menopausal women and is dependent on presence of estrogen (5).

Signs and symptoms may include (5, 6, 7):

Redness of the labia minora

Constant burning pain and/or stinging (typically around the vagina, but pain may also be felt in lower abdomen)

Positive vaginal swab for candida at ANY point while symptomatic

Typically, women with CVVC have a positive candida swab when the infection starts. After she is “treated” with a standard course of antifungal (e.g., 2 fluconazole pills 3 days apart), the swabs will be negative. However, the symptoms remain.

Soreness or “raw” feeling

Dyspareunia (painful sex)

Cyclicity (i.e., worsening in the luteal phase before menstrual period, and improving once menstrual period starts)

Exacerbation with antibiotics (i.e., worsening of symptoms while on antibiotic therapy — such as an increase in burning)

Swelling

Burning during and/or after urination

Itching (note: not always present in CVVC, and much more common in acute VVC)

Vaginal discharge (white clumpy or creamy — but also not always present in CVVC)

Previous response to antifungal therapy, even if incomplete

E.g., resolution of the itching and excessive discharge after short course of antifungal treatment (but burning pain does not go away)

E.g., Brief resolution of pain in response to antifungal treatment, but symptoms return when antifungal is stopped

E.g., a Herx reaction (candida die-off) within 48 hours of starting antifungal treatment, which often manifests as increased vulvovaginal burning and pain

Yeasty, sour, bread-like odor (note: not always present in CVVC)

Normal vaginal pH around 4.5

Bladder pain, urgency, and frequency (note: not always present in CVVC)

Worsening of symptoms with topical corticosteroids and vaginal estrogen cream

It is important to note that NOT ALL of these symptoms must be present to confirm the diagnosis of CVVC. Everyone is different. The severity of symptoms will also differ for each individual. A 2014 study found that just 4 of these symptoms together have excellent predictive validity as diagnostic criteria: history of a positive swab, cyclicity, soreness, and discharge (7).

Why is this condition so hard to test and diagnose?

The vaginal swab tests will often be NEGATIVE for candida species (2, 5, 6, 7).

Vaginal swab tests are often negative even when women have extremely painful, obvious symptoms of CVVC. Even very advanced PCR, Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), and Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing testing companies such as Evvy, MicrogenDX, or Juno can fail to detect the candida in these cases! Another common pattern may be a mix of positive and negative tests, despite a woman being symptomatic all of the time. The common finding of negative tests can be due to several reasons and will vary person-to-person:

The candida exists in extremely small amounts and is latent (not growing). Because it is such a small amount, it may not grow in culture or reach the testing threshold for detection. This will produce a negative swab. However, the small amount of candida is enough to cause this hypersensitivity response in women.

If a woman has taken antifungals (e.g., over the counter creams like Monistat or prescription medication like fluconazole), this can lead to a negative swab despite symptoms continuing. Women with this condition can find that antifungals provide some relief (even if temporary or incomplete), and use them frequently (5).

Candida can invade underlying tissues and penetrate inside epithelial (vaginal wall) cells, where they continue to release yeast digestive enzymes and toxic metabolic products that cause chronic tissue irritation. Since yeast is in the tissues and not on the surface, the swabs will give negative results (6).

Wet mount microscopy (i.e., examining vaginal discharge under a microscope) will not always show presence of yeast.

Multiple studies have shown that microscopy is not always positive in cases of CVVC, and not a reliable diagnostic test for the presence of yeast (2, 5, 6, 7). Women with CVVC are hypersensitive to even the lowest levels of candida, and it is not always guaranteed that the sample vaginal fluid being examined will show candida cells. Because candida can also exist inside the vaginal tissues, a swab of tissue surfaces (which is typically what is examined via microscopy) is unlikely to pick up that intracellular candida (6). A 2014 study found that women with CVVC had very low rates of positive microscopy examinations for their swabs — in fact, a majority had completely normal microscopy (7). The presence of white blood cells under a microscope is also not a required criteria for diagnosis of CVVC (6).

The diagnosis must be made on clinical signs and symptoms, patient history (e.g., history of positive swab), and risk factors that cause yeast infections (e.g., a course of antibiotics preceding the infection). Doctors cannot rely solely on vaginal swabs to confirm this diagnosis (5, 6, 7).

In today’s medical world, many doctors can feel uncomfortable making a diagnosis in the absence of a positive test result (especially when it comes to vaginal infections). Because CVVC will not always produce a positive swab, doctors will need to take a careful history and rely on clinical signs and symptoms to diagnose this condition, and then prescribe a trial of antifungal therapy (e.g., daily fluconazole for 3 months). Risk factors for yeast infections include antibiotics, diabetes and certain diabetes drugs, the presence of estrogen (in post-menopausal women, this is dependent on hormone replacement therapy), high sugar and alcohol consumption, immunosuppression, IUDs, sexual activity, personal hygiene practices (e.g., wet bathing suit bottoms, scented soaps), and environmental mold contamination (6).

Example case: Sarah is 24 years old, recently completed a course of antibiotics for a UTI, and starts having intense vaginal itching, burning and discharge. She does a vaginal swab and it is positive for candida albicans. Her primary care doctor prescribes a course of fluconazole 150mg, 2 doses 3 days apart. When she finishes the fluconazole treatment, her acute symptoms of itching and significant discharge subside but she is left with redness of the labia minora, constant burning, painful sex, burning with urination, soreness, and some discharge. After 2 weeks of these symptoms continuing, she returns for another vaginal swab and now it is negative. Her doctor should suspect a case of CVVC and prescribe daily fluconazole 100mg until Sarah is asymptomatic.

Note: Other example cases may include women who never test positive for candida (i.e., only negative tests), a mix of positive and negative tests, or only positive tests. Negative candida tests make it more likely that a woman will get diagnosed with vulvodynia.

Women with CVVC are very often misdiagnosed, or only given a partial diagnosis (e.g., vulvodynia) that does not address the root cause of pain. This leads to many wrong treatments being prescribed (e.g., estrogen cream, antibiotics, topical steroids, antidepressants) that can prolong the condition and even increase the pain. This shotgun approach causes greater suffering and diminishes trust in the healthcare system — so accurate diagnosis can take years or decades.

Remember that if treatments are repeatedly not working…question the diagnosis! If you give someone the wrong treatments, they will not heal. The body will respond to the right treatment.

What are common diagnoses that women with CVVC receive, when doctors cannot figure it out?

Below is a list of common diagnoses that women with CVVC receive instead, when doctors do not fully understand this condition. Note that some of these diagnoses (e.g., vulvodynia, interstitial cystitis) can be true at the same time (i.e., coexisting with CVVC) — but many doctors unfortunately fail to understand CVVC as a root cause of a woman’s symptoms.

Vulvodynia: This is a blanket term for “pain of the vulva” and not a real diagnosis that actually specifies the root cause of pain. Often, women with CVVC will get diagnosed with vestibulodynia (a subtype of vulvodynia), which means redness and pain in the vulvar vestibule and is characterized by severe pain during attempted vaginal entry (e.g., penetrative sex, tampons) (8). There are many causes of vulvodynia that are unrelated to yeast (e.g., lichen sclerosus, hormonally associated vestibulodynia, pudendal neuralgia) and CVVC should not be considered as an underlying cause in those cases. But it cannot be ignored that over 2/3 of women with vulvodynia report that it started with a yeast infection, yet many times yeast cultures are negative after the original infection is “treated” (8).

Hypertonic (tight) pelvic floor muscle dysfunction: Many women with CVVC have tight pelvic floor muscles, as they are are constantly responding to pain — therefore, prolonged clenching can lead to pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. However, pelvic floor physical therapy will not fully resolve symptoms because it does not address the underlying candida. Pelvic floor physical therapy can be effective once the candida is eradicated.

Cytolytic vaginosis, or “lactobacillus overgrowth”: This is a very rare condition caused by an overgrowth of “good bacteria” (lactobacillus crispatus, specifically) in the vagina and results in lysis (damage) to vaginal epithelial cells (11). Symptoms are very similar to CVVC, and comprehensive microbiome test results (e.g., Evvy, Juno) will often show ~95%+ lactobacillus crispatus in the vagina (12). There is disagreement in the medical community about whether cytolytic vaginosis is even real — can lactobacillus actually be the cause of a woman’s symptoms? Now, let’s talk about why the lactobacillus can be so high. There can be a dysregulated immune reaction where the body is overproducing lactobacillus crispatus to fight low levels of yeast, but cannot win. Multiple studies have shown that lactobacillus crispatus (the most protective strain) will multiply (therefore “overgrow”) as an immune response to fight candida (13, 14). Lactobacillus exerts an inhibitory effect on the growth of candida albicans (13) — but in cases of CVVC, it fails to kill the low levels of candida, so the symptoms persist. There have been many reports of women with CVVC getting microbiome test results of very high lactobacillus crispatus with no yeast detected (due to the reasons shared in previous section) — but the problem is NOT the lactobacillus, and standard cytolytic vaginosis treatments (e.g., baking soda, antibiotics) fail. Note that a similar pattern has been observed with another strain of lactobacillus called lactobacillus iners (13).

Interstitial cystitis, or “painful bladder syndrome”: Similar to vulvodynia, interstitial cystitis is a blanket term that describes painful symptoms but does not address the root cause. It means chronic pain of the bladder, along with urinary urgency and frequency — “in the absence of infection” (15). Because CVVC can also cause UTI-like symptoms and does not always produce positive test results, women with CVVC may get diagnosed with interstitial cystitis. Standard interstitial cystitis treatments (e.g., pelvic floor physical therapy, pain medications) may help with pain but will not address the underlying candida in CVVC cases. Additionally, interstitial cystitis is often misdiagnosed when doctors fail to detect an underlying chronic, embedded UTI that is actually causing a woman’s bladder pain (16, 17).

Other vaginal infections, such as bacterial vaginosis or sexually transmitted infections: Symptoms of CVVC can be similar to those of other vaginal infections, such as bacterial vaginosis (e.g., abnormal discharge, irritation, pain with sex). It is important to rule out all other vaginal infections by getting a swab test and also checking vaginal pH. A high vaginal pH of 5.0 or greater indicates the problem is more likely bacterial vaginosis or trichomoniasis (18). Note that it is absolutely possible for CVVC to co-exist with another vaginal infection, and there is a link with bacterial vaginosis (2).

Irritant dermatitis: Sometimes, things that come into contact with the vulva can cause an irritant or allergic reaction due to chemicals. This can include soaps, toilet paper, sanitary pads, tampons, laundry detergent used on underwear, fabric dyes, and more. A woman can be sensitive or allergic to these chemicals and it will cause inflammation and pain (8). This condition is not an infection, and usually resolves once the source of irritation is removed (e.g., no longer using scented tampons). If irritant dermatitis has been fully ruled out, then other conditions like CVVC should be considered.

How is CVVC treated?

CVVC is fully treatable, and with an accurate diagnosis and treatment protocol, women can completely recover from their pain. Treatment depends on the strain of candida isolated (if there is a positive vaginal swab) and susceptibility of the strain to antifungal medications. Treatment MUST be continued daily until symptoms are completely resolved (typically this takes 3 months), and then tapered down to a maintenance dose (e.g., twice weekly) (2, 5, 6, 7, 19). Because women with CVVC have a hypersensitivity (allergy) to even the lowest amounts of vaginal candida, the maintenance dose is important to continually suppress candida and prevent relapse of symptoms (19). Immunotherapy options such as allergy shots or allergy drops are also available, to avoid being on maintenance therapy indefinitely (6). While there is debate about whether diet is important, the recommendation is to avoid added/refined sugars, alcohol, and fermented foods while treating CVVC. Just following a candida diet alone is not a sufficient treatment for CVVC (6).

Standard treatment protocols to be taken daily until symptoms resolve (2, 5 ,6, 7, 19):

For infections caused by candida albicans (this represents 90-95% of cases)

Fluconazole 100mg per day orally

Itraconazole 100mg per day orally

For infections caused by candida glabrata (this is the second most common vaginal candida species)

600mg boric acid vaginal suppositories nightly (preferred option)

Other oral antifungals that work against candida glabrata such as voriconazole or ibrexafungerp

Other vaginal antifungal creams that work against candida glabrata such as a combination of amphotericin B and flucytosine

For infections caused by candida krusei, candida tropicalis, or candida parapsilosis (much less common strains)

600mg boric acid vaginal suppositories nightly

For candida parapsilosis: itraconazole 100mg per day orally

For candida krusei: oral voriconazole or an echinocandin drug such as micafungin or caspofungin

For candida tropicalis: an echinocandin drug or amphotericin B

If you don’t know which candida strain it is (due to absence of a positive swab), start with fluconazole or itraconazole

Sexual partners that are asymptomatic do not need to be treated (2)

Many doctors will differ on whether CVVC treatment should be supplemented with intravaginal antifungal products (e.g., Nystatin, boric acid), topical ointments (e.g., Mycolog), herbal / natural remedies (e.g., berberine), dietary and lifestyle changes, or other treatments. There is no universal treatment plan that is accepted by every doctor for this. It is up to the doctor and patient if alternative methods should be considered.

Maintenance protocol

Once full symptom resolution is achieved (typically this can take 3 months), then the dose is gradually reduced to the lowest level that will suppress symptoms (6, 19). This varies from woman to woman — and some will not be able to reduce their dosage at all. Most women with CVVC who reach the maintenance phase are able to suppress symptoms with 50mg fluconazole twice a week (19).

If a course of antibiotics is necessary at any point (e.g., for a UTI, ear infection), then antifungals need to be taken daily during the antibiotic course, to prevent a relapse candida infection (2).

Immunotherapy as a “cure”

Antifungal therapy will only suppress symptoms by preventing candida colonization, but it will not cure the underlying genetically-based immune system dysregulation (2). To avoid being on maintenance antifungals until menopause (and even beyond menopause if a woman does estrogen replacement therapy), immunotherapy options are available. These options include allergy shots and sublingual allergy drops that slowly help build a tolerance to candida, so the body no longer has a hypersensitivity (allergic) response (6). To undergo immunotherapy, find an allergist who can test for (e.g., allergy skin testing) and treat a candida allergy.

What should you expect during treatment?

Recovery is never a straight upward line. There will be plateaus and setbacks - keep going, you WILL heal in time.

Everyone is different. For some women, it can take two days of antifungal treatment for pain to completely resolve. For other women, it can take two months. The typical duration until a woman is completely asymptomatic is three months; however, in some cases it can take as long as 12 months (19). Some women will require higher dosages in order to see symptom resolution (e.g., 200mg itraconazole daily instead of 100mg) (5). The most important thing is to ensure that symptoms are improving over time, and if they are not improving, to revisit the treatment plan (e.g., change antifungal medications to something stronger).

This will take time.

For some women starting antifungal treatment for CVVC, the symptoms can suddenly get worse within the first few days of treatment (6, 20). Namely, this presents as an increase in the pain (burning, stinging, itching, soreness, etc.). This does not mean the infection is getting worse — paradoxically, it is actually good news! This is called the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (Herx for short) and is a temporary inflammatory response to large amounts of candida rapidly dying off. The dying candida cells release toxins faster than the body is able to eliminate them, and this activates immune reactions to antigens released from dead candida (6). Herx reactions to candida are worse in women who are allergic to candida, have high levels of anti-candida antibodies, and/or have higher loads of vaginal candida (6). To mitigate the pain of a Herx reaction, you can start with a lower dosage and build up to the prescribed dosage (e.g., 50mg for one week then 100mg, or 100mg every other day) (6). You will not “lose progress” if you slow down the treatment. It is important to get enough sleep, manage stress, drink enough water, avoid sugar, and avoid excessive physical exercise while your body is going through a Herx reaction (21). The Herx reaction usually subsides within the first week of treatment and then you will slowly start to improve (21). Even though the Herx reaction is painful, remember it means your treatment is working.

Herx reactions (candida die-off) can happen.

Questions about CVVC or want to talk about it? Reach out!

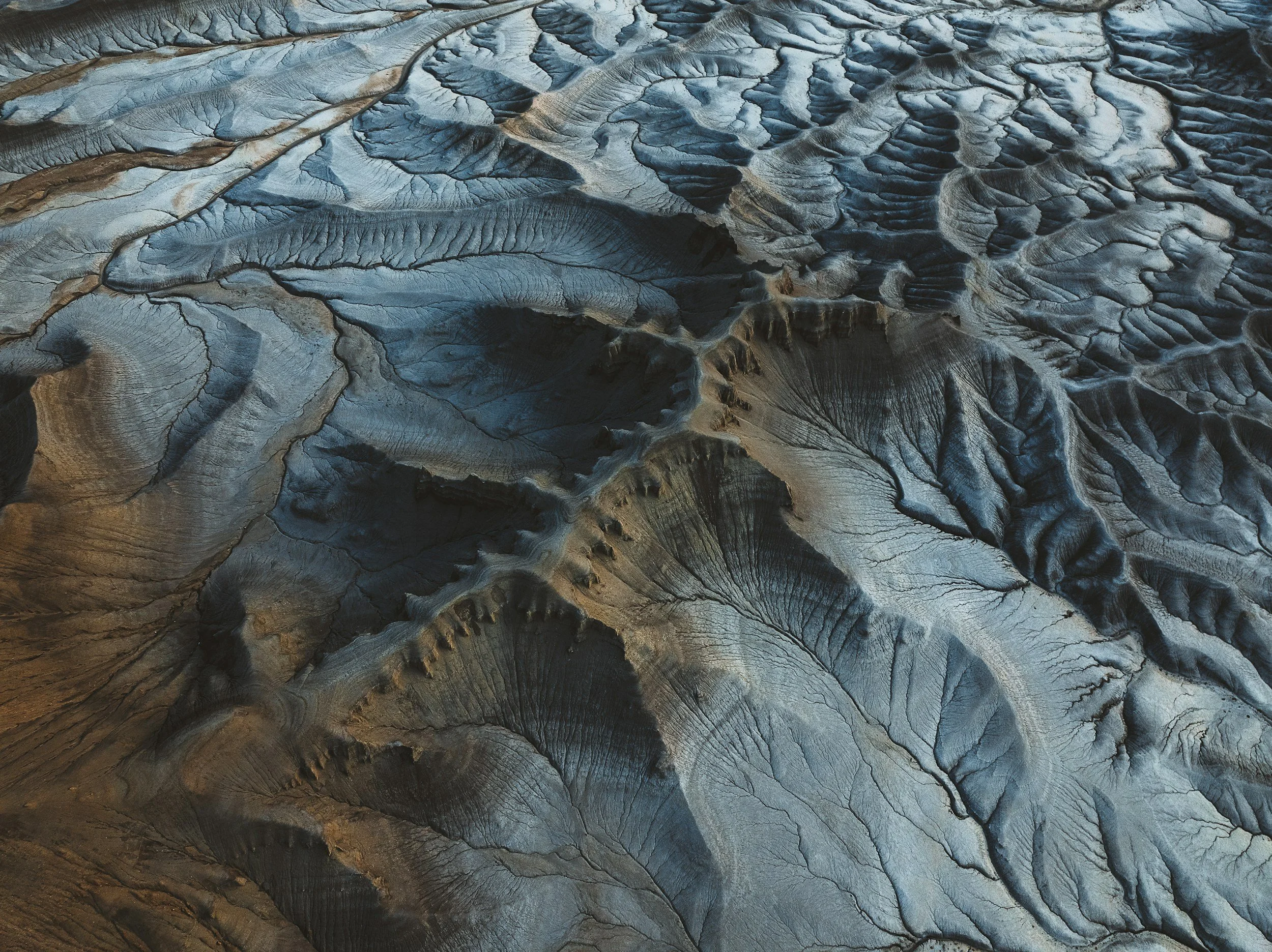

CVVC disrupted almost every aspect of my life, and the pain prevented me from truly enjoying activities I love, like hiking. It is awful that I went through this, but it wasn't for nothing. Now, I plan to use my extensive knowledge to help others.

I am a woman whose life got turned upside down by CVVC and I spent nearly a year in intense daily pain from this condition. I am not a researcher or practicioner myself. I was misdiagnosed by many doctors, given countless prescriptions of the wrong treatments that made everything worse, had to tirelessly study research papers and medical textbooks to finally arrive at the right diagnosis, and search across the world for doctors who could finally help. I am finally getting out of my pain, and this site is my project to assist the millions of other women suffering from this debilitating disease, as well as the healthcare practitioners who want to learn.